Life-saving surgery doesn’t have to be a heartstopping moment.

When cardiologists performed the world’s first percutaneous robotic-assisted mitral valve replacement earlier this year, the historic moment was notable for two reasons: First, with just a few tiny incisions, a sleek, robotic-guided system was able to accomplish a major medical feat that, for the past six decades, has almost always required open heart surgery. Secondly, when clinicians performed the pioneering surgical procedure — which could dramatically change the treatment outlook for millions of people — the moment was remarkably mellow.

“It was the calmest experience everyone involved said they have had in a case,” says Capstan Medical CEO Maggie Nixon. “That’s the power of a system that provides a clinician with so much control and precision over the procedure.”

The relative tranquility of the moment was emblematic of how Capstan aims to transform the nature of — and accessibility to — treatment for heart valve disease, a condition that currently affects more than than 7 million people in the U.S. alone. Current treatment options are limited, and aren’t widely available either due to patient eligibility factors like age and comorbidities, or simple lack of access. Open-heart surgery, the gold standard of care since the 1960s, is a highly invasive procedure that typically requires breaking the sternum, stopping the heart, and manually repairing the valve, followed by days in the ICU and months of recovery. Overwhelmed with the prospect of the procedure (which may have as high as a 10% mortality rate for some patients. Many put it off — until it’s too late. As for the alternative, truly minimally invasive options for treating mitral and tricuspid valves remain elusive. The catheter-based options for repair may not completely fix the problem, potentially leaving behind a leaking valve. Full catheter-based replacement devices that completely eliminate Mitral Valve regurgitation have limitations and are not yet commercially available — just 2% of the more than 5 million eligible patients are receiving these life-saving treatments.

Capstan exists to change the status quo by shifting heart valve replacement for those patients who have a high surgical risk into a relatively minor, precise, and low-stress procedure for both patients and clinicians. Founded and led by veteran innovators from iconic medical companies including Intuitive Surgical, Auris, Boston Scientific and Abbott, the team brings decades of experience designing, developing, testing, manufacturing, and commercializing several ground-breaking products in surgical robotics, minimally-invasive solutions, and cardiac repair and replacement. The revolutionary Capstan system represents the world’s first integration of those three discrete innovations into a single solution to treat structural heart disease.

Using the platform, doctors make a tiny incision on the patient’s hip, then drive a tube with a compressed heart valve folded up inside (similar to a closed umbrella) all the way to the heart via the femoral vein. Robotics aid the journey the entire time, using the pre-operative imaging to navigate the nuances of the patient’s unique anatomy and adjusting accordingly, enabling clinicians to place the valve in the exact right position via simple controls.

“Every patient deserves the same successful outcome,” says Nixon, who held a variety of engineering, clinical, and operations roles at Intuitive for 22 years before joining Capstan. “Our mission is to solve this by taking out the riskier components of the procedure.”

The unparalleled expertise of the executive team has enabled Capstan to move quickly since its founding. Launched under the umbrella of Capstan Founder and CTO Dan Wallace’s medtech incubator in 2020, Capstan had a proof of concept up and running by 2022. Eclipse led the company’s Series B in 2023 and the Series C one year later as the company geared up for their First-In-Human clinical trial. In March 2025, cardiologists performed the very first of these procedures with the Capstan platform in Santiago, Chile — and the second-ever procedure the next day.

“You hear the stories of the first few Capstan patients, and you feel like you can see the future,” says Eclipse partner and Capstan Board Member Justin Butler. “These are people who were struggling with daily activities, and within a few days they are feeling better than they have in years. This is what Capstan is going to deliver for millions of people.”

The company is on track to have ten implants in patients in four different locations by the end of the year, and aims to have a large-scale clinical trial underway by 2027. Commercialization could happen within the decade.

A Solution Decades in the Making

For any innovation to change a long-held status quo, it needs to not only result in better outcomes — it also needs to fundamentally change attitudes about seeking treatment in the first place, says Wallace. As the renowned developer of several transformative medical instruments that reshaped minimally invasive surgery and surgical robotics, Wallace knows firsthand what it takes for pioneering startups to radically change the face of treatment.

“Helping people when they need it usually means making it easy for them to seek out treatment,” says Wallace, who was an early employee at Intuitive and created the company’s iconic EndoWrist — one of the central technologies behind the company’s da Vinci systems.

Wallace’s career is a testament to his mission to make treatment for complex, life-threatening conditions simpler, safer, and more accessible. After Intuitive, he became a serial entrepreneur, co-founding several surgical robotics and medical implant startups that were later acquired by Auris and Abbott. Nearly simultaneously with launching the medtech incubator, Capstan was formed out of conversations between Wallace, Spencer Noe, and Evelyn Haynes, his former colleagues who worked with Dan to develop a previous heart valve. Brainstorming about how to develop better options for mitral valve replacement, they wanted to create something that would be approachable for all patients, regardless of individual risk factors and variation of the disease.

“If we can take the systemic trauma out of heart valve surgery and turn it into this comparatively minor procedure where you can go about your life within a few days, we can help a lot more people,” says Wallace.

Simplicity In Complexity

Even with the team’s extensive robotics experience, Capstan didn’t initially set out to build a robotic product. When Wallace, Noe, and Haynes built a manual prototype for what would eventually become the Capstan system, it worked — and better than anything they knew existed in the current market — but it was far too complicated, with eight knobs and levers that required more than one set of hands to operate. Simplicity would have to come from another element: Robots.

“It’s very rare to come at the problem this way, where robots actually make things less complicated,” says Travis Schuh, who joined Capstan in 2022 to lead the robotics division. “When you can create a software abstraction between the robot, catheter, and clinician, you can see exactly why robots are so valuable.”

Schuh said complexity is necessary in order to more simply replace mitral valves. Unlike the aortic valve, which is essentially a large straight pipe and can easily be replaced with a transcatheter system, the mitral valve is a 3-dimensional structure that requires navigating between two volumes. Robotics enabled them to maintain the minimally invasive nature without compromising any of the degrees of freedom clinicians needed to replace the valve, matching the clinician’s intentions with precise motion.

Soon after Schuh came aboard, Nixon joined the company, where her extensive experience scaling R&D and commercialization of surgical robotics is reaching new heights.

“There are full companies that exist around every element of what we are doing at Capstan, and that’s by design,” says Nixon. “We’re essentially three companies in one, because integrating these technologies is the only way to actually build a better treatment option.”

Integrated Team, Integrated System

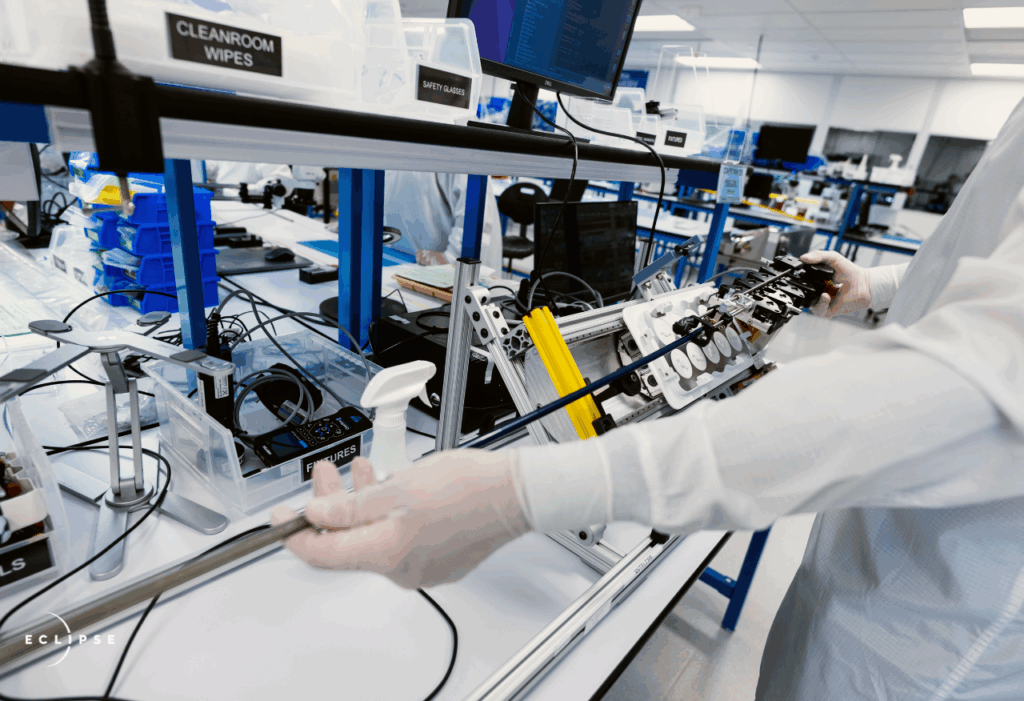

Capstan has a big vision, requiring extensive coordination across clinical, engineering, manufacturing, regulatory, and financial disciplines — almost all of which are under one roof. Housed inside the Old Wrigley Building in Santa Cruz, CA, Capstan is a place where state-of-the-art laboratories, sterile assembly rooms, robotics studios, and manufacturing floors merge with all the trappings of Northern California culture. The startup’s neighbors include Santa Cruz Bikes, various artists’ workspaces, and a company making 3D-printed surfboards from ecologically responsible materials. The building owner’s collection of vintage motorcycles lines the hallway that leads to Capstan’s facilities, where a drying rack for wetsuits stands just inside the entrance, conference rooms are named after mountain bike trails, and employees regularly bring their dogs to work.

Inside represents the past two decades’ worth of major technical and medical advances (many of which the Capstan team played an instrumental role in during their previous careers) that the company has been built upon, and is now taking the baton to drive further innovation.

An equally important tailwind is demand for innovation from interventional cardiologists, which hasn’t always been the case, says Nixon. When she began her career at Intuitive in 2000, surgical robotics was still in its early days, and the company was an 80-person company trying to break into a skeptical market. That mindset changed relatively swiftly as robotics became the primary driver of advancements in minimally invasive surgery, and the company’s technology became the default toolset for many branches of medicine like urology and gynecology. Cardiology, however, was long the holdout due to the unique challenges of the field. But now, after seeing robotics and minimally invasive surgery becoming intertwined in other fields for the past two decades and watching the rapid advancement of both technologies more recently, cardiologists are more open to robotics than ever, says Nixon.

“I was bracing myself for cardiologists to say ‘absolutely not’, but instead they said, ‘it’s about time.’” says Nixon.

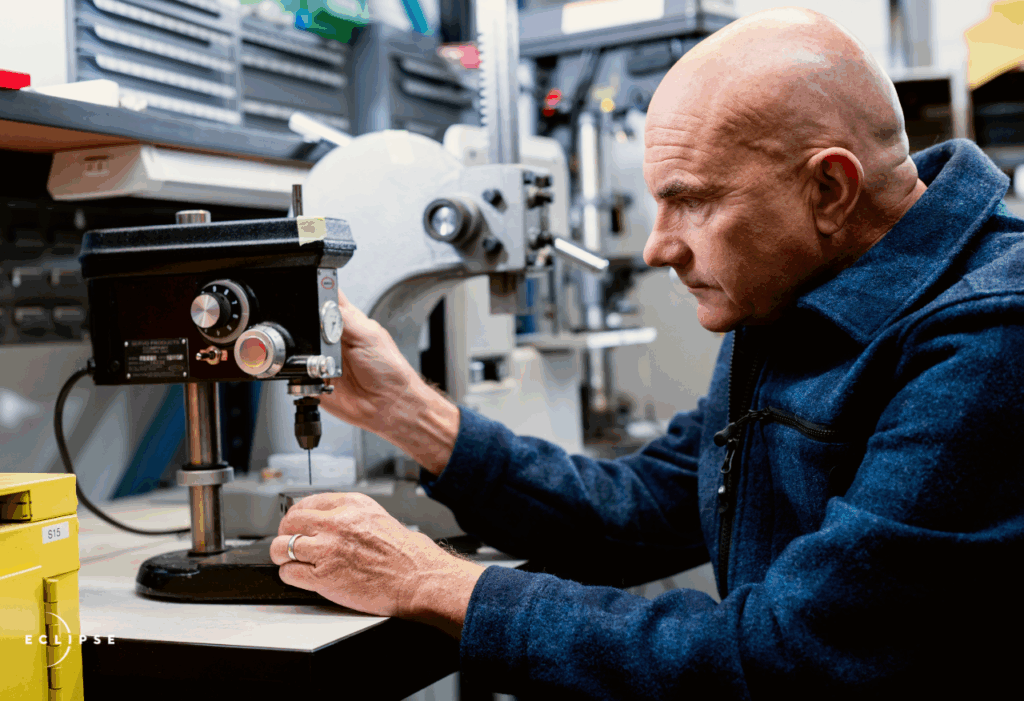

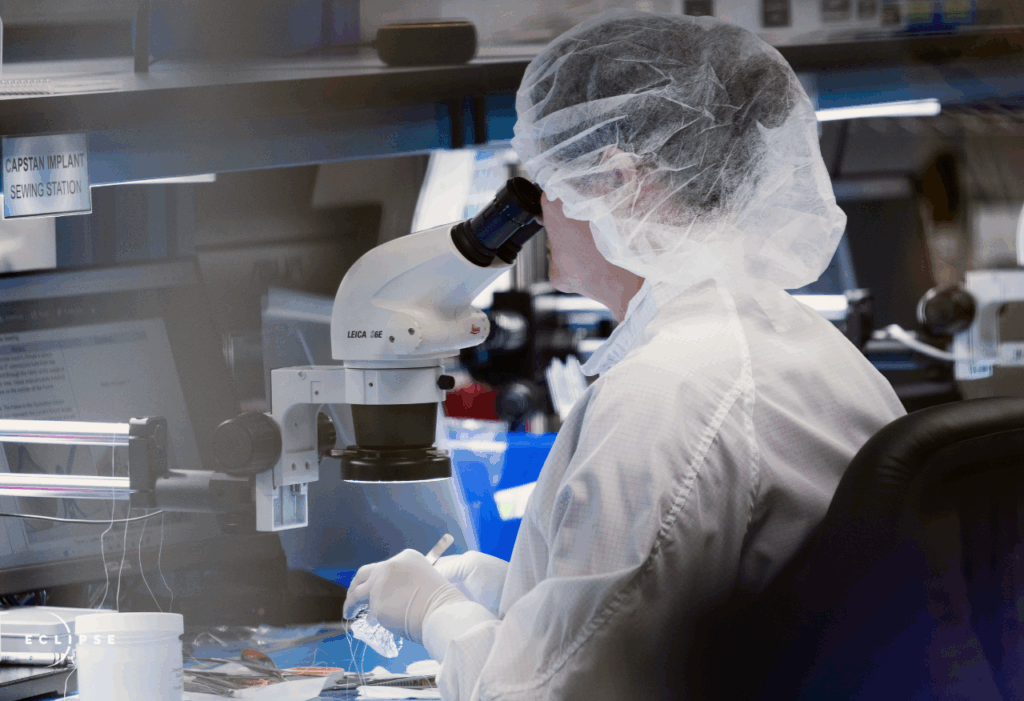

Creating each part of the system is a painstaking process. Consisting of six different components and sewn by hand in tiny, intricate stitches that must be viewed through a microscope, the implant alone takes roughly 40 hours to assemble. Down the hall, technicians put together the transcatheter delivery system (also by hand), attach the implant, then confirm the connection to the robotic arm via software interface, which analyzes for variations and automatically calibrates for uniformity.

Watching the Capstan teams in action may feel like observing artisans at work on a rare craft, but the unique detail of process — from the microscopic sewing and hand-assembly of robotics to the custom-built quality control systems — is typical for medical device companies of any size, says Nixon.

“You see these remarkably intricate, complex tasks it takes a startup to make a novel medical device? That’s exactly how it looks at the commercial level too,” says Nixon.

The difference between Capstan and a legacy medtech corporation is the speed at which the company is able to move, as well as the freedom the entire team has to focus on perfecting a single product. Since iteration requires carefully progressing each component of the system separately — but always in relation to how it fits to the rest of the platform —testing each part of the Capstan system must be set up in accordance with one another, from the pressure-testing of the valve to the responsiveness of the robotic arm.

“We spend a lot of time making sure siloes are not being built, and that’s just not something you have the flexibility to do inside a large company,” says Wallace.

Conclusion

When a condition is so prevalent that it affects tens of millions of people across the world, treatment shouldn’t still come down to access, narrow definitions of eligibility, or questions of whether it’s even worth the risk. Today, all of those reasons are why nearly a third of people with heart valve disease are never treated at all.

Capstan represents the culmination of every medical advancement that makes this reality unacceptable, packaged in a format accessible to all, driven by visionaries who’ve been working towards this moment their entire careers.

That’s why during the first-in-human procedure, the operating room was so calm, and everyone was so confident in the solution, says Haynes. There was no dramatic breaking open of the chest and essentially putting the patient’s life on hold while repairing their heart, and none of the stress and anxiety of manually guiding a catheter and implant into the tiniest of spaces.

“We were able to turn what is typically a hold-your-breath-moment into one where you could stop and have a conversation,” says Haynes, “And this is all while the patient’s heart is still beating.”

Follow Eclipse on LinkedIn or sign up for Eclipse’s Newsletter for the latest on building the New Economy